What are anxiety and depression?

Parents often experience challenges and adjustments as they navigate the perinatal period. It is when feelings of worry start to overwhelm a person and impair their ability to function in their life, that assessment or intervention for anxiety or depression might be appropriate.

Anxiety involves ongoing, overwhelming and disproportionately strong feelings of fear or worry. These feelings may happen in response to a particular situation or object, or suddenly without an obvious reason. Anxiety also involves avoiding situations or objects that may cause fear or worry.

Depression involves ongoing feelings of sadness, hopelessness or irritability. Women experiencing depression may also lose interest in and no longer enjoy activities that they used to like.

Anxiety and depression often occur together. They affect a person’s actions, thoughts and physical functioning.

Prevalence

Pregnant women with asthma report more anxiety and depression symptoms than pregnant women without asthma (Schubert et al. 2017).

The prevalence of current depression identified via symptom questionnaires in pregnant women with asthma is around 10-11% (Whalen et al. 2020, Schubert et al. 2017). Depression may be more common when asthma is more severe (Tata et al. 2007).

The prevalence of current anxiety in pregnant women with asthma has not been reported to our knowledge. However, pregnant women with asthma are significantly more likely to have a history of anxiety (46%), compared to pregnant women without asthma (24%) (Schubert et al. 2017).

National registry data indicate that 13% of pregnant women with asthma have medically diagnosed or treated anxiety and/or depression (Rejnö et al. 2019). Self-reported or medical history-derived estimates of anxiety and/or depression are far higher, putting the prevalence at 28% (Zairina et al. 2016) or even up to 45% (Grzeskowiak et al. 2017).

What is the impact?

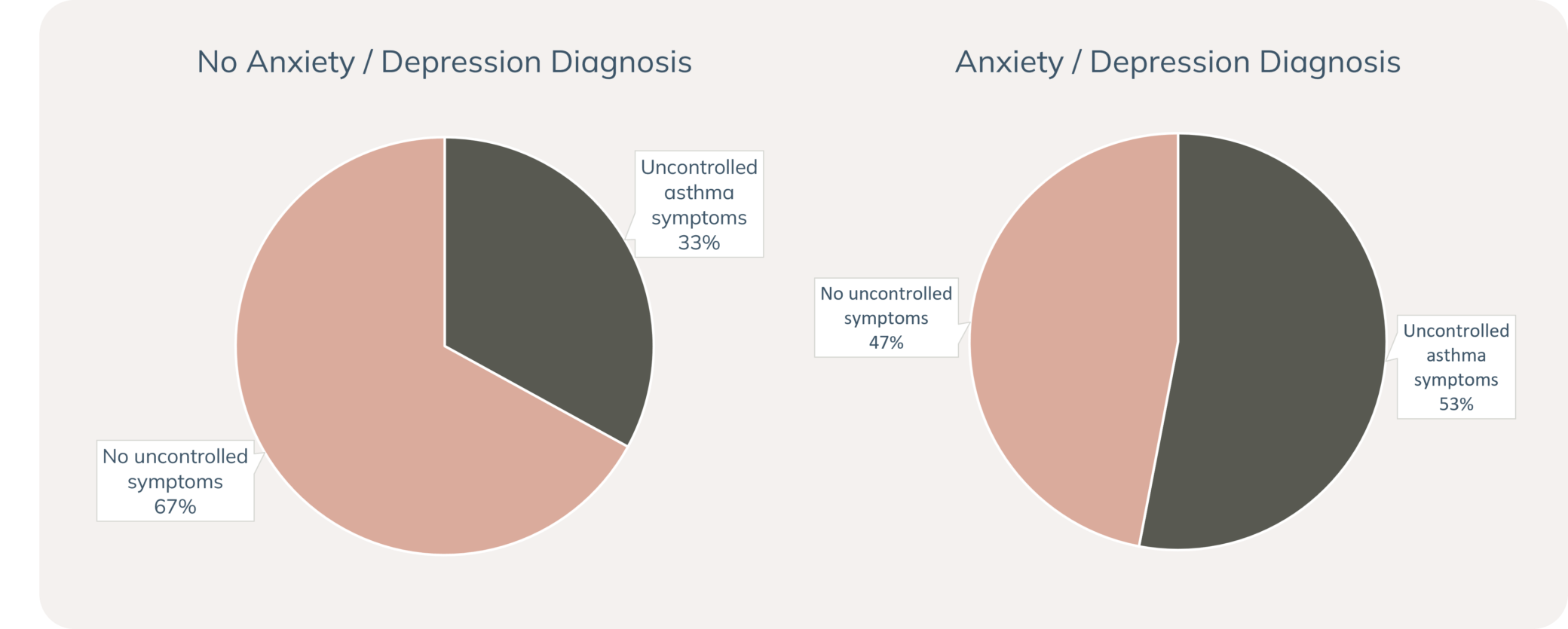

Anxiety and depression may affect asthma symptoms and asthma-related behaviours during pregnancy. Higher levels of anxiety in pregnancy may increase the risk of asthma exacerbation (Powell et al. 2013) and be associated with asthma medication non-adherence and lower asthma-related quality of life (Powell et al. 2011). Anxiety and depression may also be associated with uncontrolled asthma symptoms during pregnancy (Grzeskowiak et al. 2017). An Australian study reported that 53% of people who reported an anxiety and/or depression diagnosis had uncontrolled asthma symptoms during their pregnancy, compared to 33% in people without anxiety and/or depression. Uncontrolled asthma symptoms were also more likely to recur during pregnancy in people with anxiety and/or depression (24%, vs. 10% in people without anxiety and/or depression) (Grzeskowiak et al. 2017).

Pregnant women with asthma and anxiety and/or depression have increased likelihood of pregnancy complications compared to pregnant women without these conditions (Rejnö et al. 2019). These complications include pre-eclampsia or eclampsia, interventions during delivery (elective or emergency caesarean, instrumental vaginal delivery), and having a small-for-gestational age baby.

High levels of anxiety, depression and stress during pregnancy may also increase the risk of asthma in the child, even after adjusting for confounding variables (Cookson et al. 2009, Magnus et al. 2018).

There is currently a lack of evidence regarding the role of treatment for anxiety and/or depression on asthma in pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes for women with asthma, and these remain areas of interest for future research.

How do we assess anxiety and depression?

Anxiety and depression are formally diagnosed by assessing symptoms and impairment against diagnostic criteria and ruling out alternative causes of symptoms, such as other mental disorders or medical conditions (American Psychiatric Association 2013). Hyperventilation or dysfunctional breathing are relevant alternative or co-existing diagnoses to consider for women with asthma (National Asthma Council Australia 2022).

Although women may not meet the formal criteria for diagnosis, they may still have symptoms that are distressing and cause impairment. These women could still benefit from light-intensity intervention and are important to closely monitor.

In practice, self-report questionnaires are most frequently used to assess anxiety and depression. Routine universal screening for anxiety and depression is recommended throughout the perinatal period (RANZCP 2021, Austin et al. 2017). Women with high scores should be referred for further assessment. Women with thoughts of harm to themselves or their baby should be immediately further assessed and supported according to local policy (Austin et al. 2017).

Screening tools for assessing anxiety and depression during pregnancy

Using validated screening tools for anxiety and depression can increase the detection of problems, describe symptom severity, and inform and evaluate management plans (Radhakrishna et al. 2017).

- Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) – This is a brief and widely used perinatal depression screening tool. Scores ≥13 indicate possible depression where referral is recommended. Responses to items 3, 4, and 5 can also be used to screen for anxiety (Austin et al., 2017). Scoring 1, 2, or 3 on item 10 requires immediate assessment and arrangement of support, guided by local protocols where relevant. Information on suicide risk screening is available here.

- PANDA mental health checklists – These checklists can be helpful to start conversations around anxiety and depression with pregnant women.

- Antenatal Risk Questionnaire – This tool is designed to assess a broad range of psychosocial risk factors, including anxiety and depression.

- Other questionnaires – Other validated questionnaires that you may be familiar may also be appropriate for screening in pregnant women, such as the Kessler-10 (K10) Psychological Distress Scale or the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale.

How do we manage anxiety and depression?

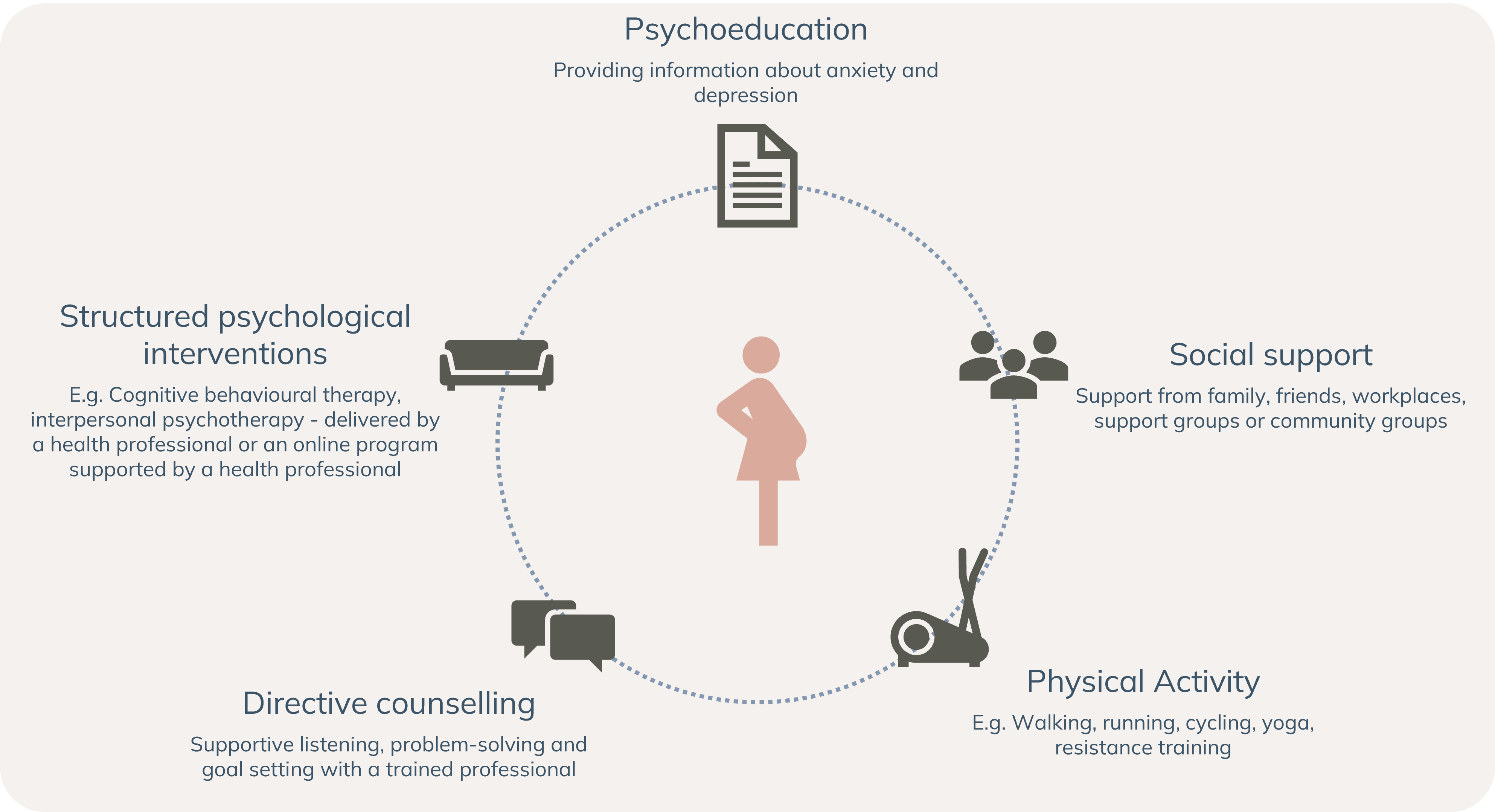

Early intervention may help prevent more serious problems from developing. There are a range of evidence-based options for treatment of anxiety and depression, including counselling or psychological therapies (delivered face-to-face, online, or via telephone) and pharmacotherapy. General practitioners may be a good first point of contact for accessing this kind of support.

Social support from family, friends, workplaces, support groups or community groups is also very helpful. Women with anxiety and depression may also find benefits in engaging in physical activity, meditation, relaxation, healthy eating and good sleep hygiene.

Supporting emotional health and wellbeing during pregnancy.

Adapted from: Austin M-P, Highet N and the Expert Working Group. (2017) Mental Health Care in the Perinatal Period: Australian Clinical Practice Guideline. Melbourne, Australia: Centre of Perinatal Excellence.

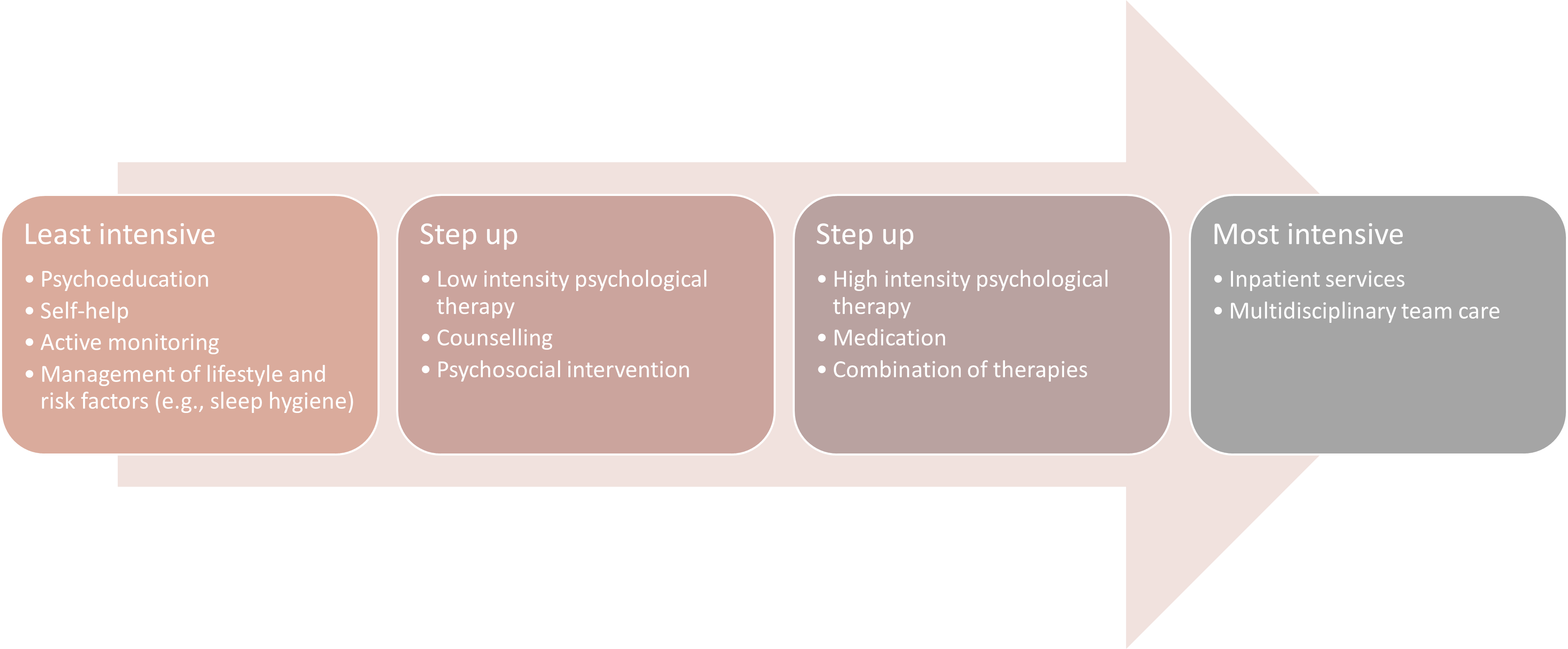

Stepped care for psychological intervention is recommended, whereby women are offered the least intensive treatment that might relieve their asthma and depressive symptoms, with treatment increased to more intensive treatments if symptoms do not improve (Malhi et al. 2015, Austin et al. 2017). Treatment of moderate-severe anxiety or depression might involve a combination of antidepressants with a low-risk profile during pregnancy and psychological therapies (Austin et al. 2017).

Stepped care for anxiety and depression. Adpated from Malhi et al. 2015; National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2011.

There are several options for specialised support for women experiencing anxiety and depression in the perinatal period in Australia.

- PANDA operates Australia’s national specialist perinatal helpline, which individuals can call to connect with trained counsellors for support and information. Their website has useful information on perinatal anxiety and depression for health professionals, patients and their families. Health professionals may also refer to PANDA’s telephone-based programs.

- Gidget Foundation Australia has several programs to support women experiencing perinatal anxiety and depression, including online support groups and telehealth (accessible via GP referral).

- Specialised perinatal mental health services may be available through local health districts, including outpatient, inpatient and telehealth services. Please check what is available through your local health district or state health service.

- Online programs and apps: The Australian Government’s Head to Health website catalogues online programs, apps and websites that may be useful for women experiencing anxiety or depression during pregnancy, such as:-

- MindMum app (free phone app with information, strategies and activities),

- Mum2BMoodBooster (free online treatment program; 6-sessions based on cognitive behaviour therapy), or

- MUMentum Pregnancy & Postnatal Course (free with clinician referral: 3-lessons centred on psychoeducation and cognitive behaviour therapy).

For women in crisis or at risk of suicide, there are 24-hour crisis counselling services available over the telephone or online. In Australia, this includes:

- Lifeline: 13 11 14

- Suicide Call Back Service: 1300 659 467

- 13YARN: Specifically for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island people: 13YARN or 13 92 76

Useful Australian resources:

Key considerations for Specific Populations

Indigenous Populations and Minority groups including refugees, culturally and linguistically diverse populations

Culture and language influence how mental health or social and emotional wellbeing are conceptualised, understood and experienced. Providing culturally safe assessment and management of anxiety and depression is paramount. Engaging with organisations such as local Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services, Primary Health Networks, or Transcultural/Migrant/Refugee Health Services (see also these resources) is recommended to facilitate culturally safe mental health assessment and care. Consider the appropriateness of screening tools in terms of language and culture (Austin et al. 2017). There are translations of screening tools such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (including locally developed versions for some Aboriginal communities) and different cut-off scores for different culturally and linguistically diverse groups, which might be appropriate for some women.

Remote and Rural Health

Face-to-face mental health services in rural and remote communities can be limited. Helplines and telehealth services, such as PANDA and the Gidget Foundation, or online treatment, such as the Mum2BMoodBooster treatment program, may be useful ways to access support in these communities.